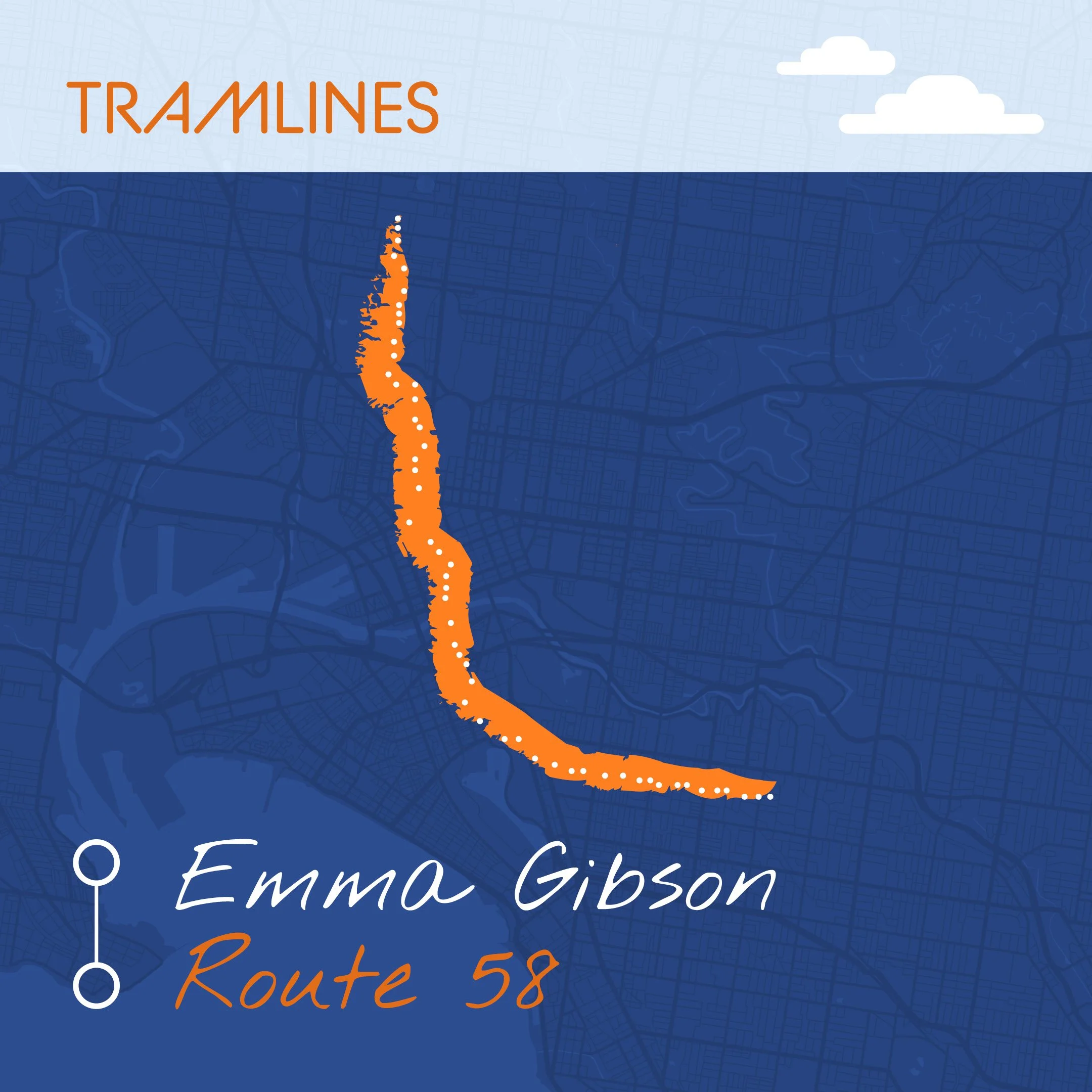

Route 58: Emma Gibson

Image by Connor O’Brien

Route 58: Happily, Ever Future by Emma Gibson

In the near future, Melbourne is selected for a bold experiment to solve a wicked problem plaguing urban planners around the globe: will jamming mobile phones during peak hour commutes improve safety?

Ash and Gem are regular passengers on the tram. Without screens to distract them, they make a connection, opening up the possibilities of further adventures together, but once normal mobile phone service is resumed, will they lose sight of one another again?

You decide the ending depending on which stop you depart at.

The optimum place to listen to it is on the route 58 tram, starting at stop 45, Bell Street and ending at stop 4, Collins Street, but it can be listened to on any tram at any time.

Credits

Written by Emma Gibson

Commissioned by David Ryding

Edited by Elizabeth Flux

Recorded at the State Library of Victoria

Produced by Beth Atkinson-Quinton

With music by Steve Hearne

Tramlines is a podcast created by Broadwave in partnership with the Melbourne UNESCO City of Literature Office.

Get in touch

We love hearing from our listeners. Stay in touch across Twitter, Instagram and Facebook at @broadwavepods, and @MelCityofLit on Twitter.

Route 58: Happily Ever Future by Nadia Bailey

West Coburg from Bell Street to Flinders Street

[SFX A tram travels towards the listener. Rumbles along the tracks. People board.]

Intro (various voices): Tramlines, Tramlines, Tramlines (laughs), Tramlines, Tramlines, Tramlines, um T-R-A-M-L-I-N-E-S, Tramlines.

[SFX Tram doors open]

Beth Atkinson-Quinton VO: This is Tramlines: part audiobook, part spoken word and part locative literature. These are stories written to be listened to on a tram.

[SFX Tram dings and journeys on. Theme music fades out. Episode theme opens]

Beth Atkinson-Quinton VO: Today’s journey is a new fiction work by Nadia Bailey. The optimum place to listen to it is on the route 35 tram, starting at stop D2, Central Pier, but it can be listened to on any tram at any time.

Bell Street to Reynard Street

[Approx. 2 min]

This story hasn’t happened yet. But a few years from now, despairing city planners around the world will be pondering the possibility of technological intervention to improve public safety for peak hour commutes. Accidents on public transport will be increasing and the culprit is clear: commuters distracted by their mobile phones, screens, or other devices.

Public safety campaigns won’t have achieved results — but will depriving people of their devices, even for a short time, change their behaviour?

An international city innovation lab proposes a trial using new technology on public transport that jams the signal on all electronic devices — from smart watches to e-readers — effectively turning them off. It’s a bold experiment and Melbourne, being a bold, progressive city, agrees to take part.

There’s public consultation and no one protests too loudly, although one of the telcos launches an ad campaign encouraging people to work from home, rather than face an “unproductive” screen-free commute.

And so today, the first day of the phone-jamming trial, Ash gets on the 58 West Coburg tram at Bell Street, and with fewer passengers than usual, takes a seat towards the back.

Ash often works from home — what with the price of office space, most workplaces encourage hotdesking. Ash’s supervisor, Gary, who eats constantly and talks with his mouth full, has the unfortunate habit of leaving behind smears of mustard, sandwich crumbs, and flecks of spat-out tuna on every desk he occupies.

Today, Gary aside, Ash is looking forward to working in the office — to wearing tweed instead of trackie bottoms — and most importantly, to the commute. As the tram trundles along Melville Road, Ash keenly observes how other passengers are responding to the Tech Jam. Some people are still reaching for their phones, hopefully or habitually, then discovering their screens blank. No one knows what to do with their hands, or where to look. There’s a lot of awkward accidental eye contact, with heads quickly turning away.

Woodlands Ave to Moreland Road

[Approx. 2 min]

Ash is hoping for conversation, but it doesn’t eventuate, and as people revert to gazing out the window at the California Bungalows they’re passing by, Ash pulls out a book.

At Moreland Road, it’s standing room only when Jem boards the tram with a coffee in one hand and a book in the other. Ordinarily, Jem would also have earbuds firmly clamped in, but the phone is dead, blank, useless, just like everyone else’s, even though Jem is a software engineer who works for a major phone company. Jem had, of course, looked for a vintage yellow Walkman in a bid to go analogue, but could only find unethical reproductions, so the book alone will have to do. Jem usually cycles to work, but the bike is in for repairs. Jem’s wearing Docs and vintage jeans — because that will still be the fashion in this future Melbourne, although the vintage may have changed — and is one of these people who seems to have perfect balance, standing in the middle of the tram, with full hands, holding onto nothing, except the coffee and the book. The coffee is an ethically sourced long black in a ceramic cup, and the book is from a second-hand bookstore in Brunswick. It’s an obscure title of obtuse fiction by a celebrated international writer who achieved posthumous cult status: that is, most people have never heard of the author or the book. Due to the time in which this author was published, and international rights and translation and the author’s paranoid estate, most of the published works never leapt across to digital editions, leaving afficionados to prowl through second-hand stores in the hopes of finding a battered paperback. Jem’s own copy has a split spine, where the yellowing glue has cracked, and a segment of pages threatens to fall out. Jem was the kind of kid who would work at a wobbly tooth until it came out, not content to wait for it to fall out on its own. Jem as an adult has learned to resist this, learned to wait to see how things fall into place.

So, when Jem notices Ash, wearing tweed slacks and a paisley button-up, leaning intently into the exact same edition, it’s a struggle to resist the urge to interact, to interrupt and point out that they are both reading the same book.

Mattingley Crescent to Hope Street

[Approx. 3 min]

Ash is engrossed in the book and doesn’t look up, doesn’t notice Jem, doesn’t notice the twin edition, and so Jem begins reading too, and when more passengers get on at Mattingley Crescent, and Jem automatically moves back down the tram to create space, ending up right next to Ash, Jem is now too busy reading to notice the proximity. Maybe they are even reading the same chapter — the same page as the tram passes Jacob’s Reserve.

Then the tram driver slams on the brakes in the way that usually only happens when a vehicle cuts in, bell clanging indignantly, jolting the standing passengers. Jem, who usually has perfect balance, even with a coffee in one hand and a book in the other, lands half on Ash’s lap. It seems to happen in slow motion — oh no, the hot coffee! Jem tries to keep the cup upright; Ash braces Jem’s arm, grabs the cup. The tram is suddenly still.

“Sorry,” Jem says, sprawled across this stranger’s lap.

The tram driver belatedly plays the “in traffic, sudden braking may be necessary” announcement.

Jem and Ash look at each other and laugh. Ash notices that Jem has remarkable eyes, like jewels.

“Are you okay?” Ash asks, helping Jem up.

“Yeah. Are you? Thanks for catching me. And saving the coffee.”

Ash is still holding the coffee and hands it to Jem. Jem notices that Ash’s paisley sleeves are rolled up, revealing a forearm tattoo of an avocado.

“Purely selfish. I just didn’t want to get coffee on my book,” Ash says with a smile. Ash has a great smile. Like the kind of smile babies do, miraculous and full of wonder. Ash retrieves the book from the floor and then repeats the motion, coming up with a second one, a duplicate. It’s Jem’s.

“It’s mine,” Jem says.

“Snap!” Ash beams. “I’m reading the same book. The same edition.”

Jem knows this, of course, but decides to play it cool.

“Well, make sure you don’t mix up the copies — mine has a broken spine.”

Ash hands Jem the book. Jem’s eyes are drawn again to the tattoo on Ash’s arm.

“What are the odds?” Ash says. “Have you read it before?”

“No, I’ve been reading them all in order of publication,” Gem replies.

“I haven’t read all of the back catalogue, but this is my favourite so far,” Ash holds the book tenderly. “It’s my second time reading it.”

“So, you know how it ends?” Gem asks.

“Then, we can’t talk about much more. Unless you want spoilers.”

“Definitely not.”

So they talk about other things. The conversation is free-flowing, easy, and they’re both interested in what the other has to say.

This moment is what Ash has been hoping for. Human connection, eye contact.

Victoria Street to Daley Street

[Approx. 3 min]

This conversation is the type of conversation Jem has been craving, instead of talking about housing affordability and the economy, or droughts, fires, and sudden storms. Jem wants to continue the conversation, but as the tram sways around the corner after the Smith Street stop, Jem, who is usually well balanced and who, for that reason, isn’t holding onto anything, staggers slightly away from Ash. As the doors open at Daly Street, the passengers shuffle to make space for an elderly gentlemen boarding. Ash stands and offers the man the seat, and other passengers close in the space between Ash and Jem. Separated, they return to their books, stealing surreptitious looks at one another.

Jem wonders about the tattoo — does it symbolise home ownership, something Jem still doesn’t dare dream about? Or does it mean something else entirely? Jem has a sudden, strange desire to touch the tattoo, to feel the avocado-inked skin.

Ash peeks up at Jem, wondering if those incredible eyes are natural. Maybe coloured contacts? Ash tries not to judge people on their appearance and is usually attracted to someone for an intellectual, rather than physical connection. And yet, those eyes.

Jem looks up, catching Ash’s gaze, and because neither of them wants to be caught looking away, they lock eyes for a moment, and both do the tiny twitch of the lips that people do in acknowledgment.

Returning to the book, Ash reads the same page three times in a row, retaining nothing. Jem’s pulse has quickened, a higher BPM than usual, loud as music in Jem’s ears in the absence of the usual earphones.

The next day on the tram, Ash again takes a back seat and again sees Jem board at Moreland Road — coffee in one hand, book in the other. As the tram fills, Jem inches towards Ash’s seat. They nod in acknowledgement.

Ash thinks about making a joke about no lap being available today but decides that would be over-familiar.

Jem thinks about pretending to fall again, but thinks the better of it. They both wonder about initiating conversation; both return to their books. When the announcement about “sudden braking” plays, they exchange a look, and smile. And just like that they start talking again, until they are separated as the tram fills up, and as Ash offers the seat to others.

On Wednesday, another passenger notices the two of them reading the same book and points it out, starting the conversation for the two of them.

On Thursday, they are both wearing green jackets, because it’s supposed to rain (but doesn’t) and they brandish their matching jackets and books and say “snap” and lean into one another to talk. A routine is beginning to develop.

Then on Friday, it pours with rain.

Foden Street to Union Square

[Approx. 2.5 min]

On this particular day, Ash has vacated the seat for a pregnant woman, and as the tram passes the Grantham Street stop, is trying to find a spot standing closer to Jem so they can continue their conversation. Jem has been hemmed in next to the door. With three people standing between them, Jem eventually returns to reading the book in one hand, and sipping from the coffee in the other. Ash doesn’t have the balance that Jem does, needs one hand to hold on to something and ideally, prefers two hands to read a book to avoid cracking the spine. So instead of reading, Ash watches Jem reading, wondering what part of the story Jem is up to. Ash has also decided that Jem doesn’t wear contact lenses — those luminous eyes are real. Not that appearance should matter, of course. As the tram stops at Union Square, Jem flips to the next page and maybe it’s the extra humidity in the air, or merely an eventuality, but the glue in the split spine of the book finally fails. The loose tooth falls out. A whole segment of pages sails out the tram’s open door… and into a puddle. Ash sees this happen; tries to do something to help, lunges towards the door too late to catch the book — but ends up standing next to Jem.

“Did you see that!?” Jem asks.

“It just flew away.” Ash replies.

“Like a paper bird.”

“Yeah. Sorry about the nosedive into the puddle.” Ash says.

“I just got up to that section too.” Jem sighs.

“Can I see where you’re up to?”

Jem holds out the book. Ash compares their copies.

“I’ve finished reading that bit,” Ash says. “We can swap books?”

Jem hesitates — “Are you sure? It’s raining, and the book could get wet—"

“It’s fine.”

“And how will we swap the books back?”

Yes, the book presents an opportunity for them to meet again, the promise of future conversations. Ash had not even considered this possibility in making the offer. Sometimes an act of kindness really pays off.

“We’ll just have to see each other on the tram again.” Ash says, with a smile.

Ash really does have a magic smile. Jem marvels at it, at the way Ash’s whole face lights up – and Jem can’t help but smile back. “It’s a deal.”

They swap.

Brunswick Road to Melbourne Zoo

[Approx. 3 min]

Jem and Ash both pretend to resume reading. It’s a weird thing to do, and yet, it feels safe to hide behind their books. They are standing so close together it feels almost too close to keep talking, almost too intimate.

Ash has a moment of anxiety, a butterfly at the throat, wondering, should we swap details? But the butterfly gets stuck, stopping Ash from trying to talk. Be cool Ash. Be cool. Read the book.

Jem, turning the pages with a practiced one-hand flip, grazes against Ash’s arm. Even though there’s a layer or two of fabric, it feels electric, charged. Jem can feel the warmth coming from Ash’s body, thinks of that avocado tattoo, imagines what it would taste like.

As the tram slides into Royal Park, Jem is imagining picnics, a visit to the zoo, bicycle rides together, and making Ash smile — being the object of that smile. It’s not fantasising exactly. As an app and game developer, Jem’s instinct is to model potential future scenarios. Jem’s brain reels through those possibilities.

Meanwhile Ash, who adores alliteration, begins hearing love poems in the rhythm of the moving tram, begins imagining how the text of a shared life might unfold, imagines their two names being appended, that coupling of words making a unit of two people, and isn’t the word ‘and’ amazing – Ash and… Jewel-eyes — And Ash thinks there’s so much possibility here. In rom coms they have this thing called a “meet cute” — as though it’s the moment the two lovers clap eyes on one another that will set the tone for their lives, and a stranger tumbling into — no, landing in — Ash’s lap is just that type of meeting. Ash thinks, isn’t it funny, how we talk of falling in love, as though a physical force, or an accident. You might think, who meets the love of their life on a tram anyway?

Ash recalls the story of two trams that kissed and were married. That is, the trams collided, not on the 58 route, but on the corner of Nicholson Street and Victoria Parade. They were B2 class trams — the type with two carriages and a concertina join. The front end of one tram and the back of the other were damaged. In the workshop, the undamaged halves were coupled together and returned to service as tram number 2059, the tram that had been hit in the collision. The two damaged parts were later repaired and put together, taking the name of the other tram, 2057. Both trams still service the 58 route. True story.

So, look up for the number of the tram you’re riding in right now it’s possible you are sitting in tram number 2057 or 2059. Maybe Ash and Jem will be too on this particular day, at this particular time as the tram snakes through the park. They’ve been caught unaware, just like the trams were. Two lives, colliding.

State Netball and Hockey Centre to Royal Park

[Approx. 3 min]

Coming over the crest past the State Netball and Hockey Centre, the tram slows. Then slows some more. It’s not just about wet weather and slippery tracks, Ash thinks, imagining sand scattered on the tracks for traction as the tram edges... slowly… to a stop.

Ahead, a flash flood has turned Flemington Road into a canal.

The tram is stranded in the park, next to the Royal Children’s Hospital.

The tram driver makes an announcement. They are waiting for the flood waters to be cleared. No news yet on how long that will take. There is nothing to do but wait.

People begin to do what they would ordinarily do — whip out their phones to check for an alternative transport option, inform their boss that they’ll be late because of public transport, complain to their friends, or kill some time on social media — but of course, their phones are still blocked, even though the tram is stationary.

The tram is crowded and humid.

Jem considers possible scenarios for this moment. How disquiet will grow, becoming impatience, anxiety and then panic. Especially without phones.

Ash worries about this too. Stuck, still, surrounded by floodwaters and no communication line out.

People have started spending their commuting time reading books, knitting scarves, sketching in notebooks — and Ash has even heard of some trams holding ukulele sing-a-longs. Ash wonders if anyone on this tram has an instrument. Or can tell jokes or do card tricks. Any distraction to cut the tension.

“Has anyone got a ukulele?” Ash asks, although no one but Jem pays any attention.

Suddenly, there’s a commotion in the back end of the tram. A surge of voices saying someone is having an asthma attack.

An emergency. And no one can use their phone. Panic rises.

“Has anyone got an inhaler?” Ash asks, and this time, people do pay attention. Further down the tram, someone fumbles for an inhaler and passes it along. People make space around the person — it’s the pregnant woman that Ash had earlier given the seat to. She’s panicked, struggling to breathe, doesn’t want to take the inhaler.

“Maybe it’s not asthma, maybe it’s labour?” someone says.

“Any doctors on board?” Jem asks.

Ash calls along the carriage to ask the driver to contact emergency services, and finally, when nothing happens, asks to get the door open.

And Ash dives outside, onto the soggy ground — that corner of the park next to the Royal Children’s Hospital has turned into a pond — and runs into the pouring rain, trying to get far enough away from the tram’s jamming technology to make a phone call.

Everyone on the tram waits like damp, anxious sardines, completely useless. When medics arrive to help the woman, Jem helps to get her out of the tram, squelching through ankle-deep water.

Royal Children’s Hospital – Royal Melbourne Hospital

[Approx. 5 min]

Ash and Jem re-board the tram to applause from the other passengers. And moments later, the scene clears: the clean-up truck finishes sucking the water from the tracks and the tram finally moves again… only to stop at stop number 19, Royal Children’s Hospital. Ash and Jem step away from the doors to let other people out, and someone says thank you and they both overhear themselves being described as “that helpful young couple” by someone elsewhere in the tram and both think, “yeah, why not,” and both want to suggest coffee and a debrief — somewhere warm to dry off, an opportunity to get to know one another better. But then the person talking about them continues the sentence — “If it wasn’t for them, I don’t know what would have happened. The tram driver said he couldn’t get through to dispatch because it was too busy. Think about it, all those emergency calls being funnelled through that system instead of people being able to call themselves.”

Ash and Jem instantly forget about getting coffee. They have both realised something. For Ash, it’s a problem and for Jem, it’s an opportunity.

Ash works in public relations at the Department of Cities, Infrastructure, Transport and Information Technology — or affectionately known as “Cit-In-Trans-It”. See, Ash has a vested interest in the commuting technology jam, because Cit-In-Trans-It is leading the trial.

As Ash arrives to the office, Gary is already there, chewing on an egg and bacon roll. Gary has continued to colonise the office, abandoning one desk for the next when it becomes too disgusting.

“We have a problem,” Ash says.

“I know,” Gary says, his mouth still full. He has a dollop of egg yolk on his tie. “They’re not happy. Big bloody surprise. As though we didn’t warn them. Revenue’s down on public transport. Significantly. Budgets being recalculated. Boffins scratching their heads in bewilderment.” Gary, apparently unaware that some could consider him a boffin, scratches his head. “Can’t please some people. They ask us to improve public safety, we do, and now they say it’s fiscally unsustainable.”

“More to the point — there’s a safety issue,” Ash says.

“What?”

“There was a medical emergency on my tram this morning. The tram driver couldn’t get through to dispatch because it was so clogged up —"

“So, what happened?”

“I ran out into the rain to use my phone.”

“Oh, that’s why you look like that.”

Ash ignores the comment. “The point is there’s a real perception issue around of duty of care —"

Gary interrupts. “It’s a moot point. We’ve got to find a way to kill the trial.”

“What?”

“Like I said. Revenue. Better get your thinking hat on. We have until tomorrow to come up with a solution to pull the trial while still saving face.”

“To be fair, the trial isn’t a failure — it’s just achieved the purpose of a trial and collected its most important data.”

“Minister won’t see it that way. Media won’t see it that way. Have you seen the ad campaign one of the phone companies is doing? Myki card in a lock and chains?”

Ash has an idea. “What about an app that bypasses the jam? Let people download the solution.”

Gary grins. “We’d have to go through a third party — maybe a telco. I know someone. Leave it with me, kiddo.”

And later that day Jem is pitching a new app.

“I was on a tram this morning and there was a medical emergency and for some reason, the driver couldn’t get through to dispatch. Another passenger sprinted through the pouring rain to get far enough away from the jamming signal to make a call. We want to ensure our customers can access emergency calls. That’s why we’re developing this app, which will allow phone calls to bypass the technology jam and improve safety.”

One of the Directors raises her hand.

“Yes, Mariam.”

“If we’re opening up a bypass for people to be able to make calls, why not just bypass the jam completely?”

Gary had contacted Mariam earlier in the day, outlining the problem — and Jem’s app could be just the solution.

Mariam continues. “Obviously the company wouldn’t want to encourage our customers to disobey a government-imposed tech ban on public transport. But would this app open up that possibility?”

Jem speaks carefully. “Our app is only for emergency calls. But if other tech-minded people out there wanted to piggyback off it… yes, it’s possible others might find a way to bypass the jam.”

Everyone in the room suddenly realises the opportunity to regain lost revenue by giving people a way to use their devices on the commute again.

Mariam asks: “How long before we can have it in the market?”

Flemington Road to Queen Victoria Market

[Approx. 2 min]

Two weeks later. Normal service has been resumed, thanks to the app. It started gradually, with a few people here and there surreptitiously checking their phones, and then more, people still unsure whether they were allowed to be using them, whether they could get fined. But soon, screens on commutes had returned almost back to normal. Now, commuters who downloaded the app think they have outsmarted the trial, to the relief of Ash and Gary who will soon be able to switch off the expensive jamming technology. The tram is getting busier in the mornings again, and with so many people on board, Ash and Jem haven’t seen one another since the day of the flood.

This is partly because they’ve both been working extra hours lately. Ash has been going in early to get a jump on the negative media that has been coming out around the jam — surprisingly the key criticism has been that it was called off early, after the black market app rendered it futile. And yet, some of the other participating cities around the world have also concluded their experiment early — for different reasons, but using the same solution — an app leaked by a third-party developer. Gary’s been pitching it on the downlow to international equivalents, and he’s received high praise for it. He’s been seconded to a new project — with his own office.

Now, Ash sees a passenger slipping a lanyard with a security pass around their neck and suddenly thinks of a company logo in Gary’s presentation about the jam-blocking app. It had seemed familiar. Now Ash remembers seeing the logo on Jem’s work pass.

Jem’s been staying back late. There’s been a lot of extra work, adapting the jam-blocking app for different markets. It’s been a real win for the development team, although Jem is now looking forward to working on something new.

It’s usually dark when Jem travels home, wondering if Ash will be on the tram — and maybe a casual after work drink could eventuate — but Ash is never there.

Will Ash and Jem find each other again? You, the listener, will decide the ending, depending on which stop you leave the tram.

Ending 1: Flagstaff Station

[Approx. 2 min]

If you’re getting off the tram at Flagstaff Station or before, here’s how the story ends.

Ash and Jem are still looking out for one another. Ash has been trying to find Jem through the company directory — but the telco has as more business arms than an octopus, and thousands of employees.

Jem’s been looking for Ash too. At first, Jem had tried to cut down on screen time, but once everyone else on the tram was back to scrolling through their phones on the commute, Jem started doing the same. Not scrolling, but swiping. Jem has been going through all the different dating apps, looking for Ash’s face. For that smile.

One day, Ash finds Jem. Not in a company directory, but on the tram. They’re already on Peel Street when Ash gets a glimpse of Jem at the other end of the packed tram, coffee in one hand, phone in the other, earphones in.

Jem is intently swiping through an app, eyes glued to the screen.

In a moment, Ash will get off the tram at Flagstaff Station to go into a job interview for a promotion.

Ash wills Jem to look up. Jem does not.

In the days that follow, Ash will be promoted to Gary’s old job, and go back to working from home more often.

Jem’s bike will be fixed, finally. It’s a steel-framed vintage three-speed, with a milk crate on the rear rack and a 3D-printed coffee cup holder on the handlebars. Jem will go back to cycling to work most days.

Whenever either of them happens to be on a tram, they look for the other, and occasionally, for a moment, think they get a glimpse, but it’s someone else entirely.

Over time, they will stop looking.

Maybe Ash and Jem will see one another again, years later, a glance across a crowded tram, but neither of them will recognise or remember the other.

This is a cautionary tale and a reminder to look up, because you never know who could be looking back at you.

Ending 2: Lonsdale Street

[Approx. 3 min]

If you get off the tram between Lonsdale and Collins Streets, this ending takes place along Bourke Street.

Because for some reason, although it’s not their usual stop, on this particular day both Ash and Jem alight at Bourke Street and after getting across William Street, see each other through the crowd of people.

They’d looked out for one another of course, it’s become habit. Somehow, they didn’t see each other on the tram. Yet here they are. Ash waves. Jem waves back. Neither of them is entirely sure if the other has waved to them, but neither wants to look over their shoulder. And without even really thinking about it, the two of them start walking towards each other, hesitant. But as the distance between them closes and they both realise that the other is looking at them, that they are moving towards one another, Jem brandishes Ash’s copy of the book, and then Ash produces Jem’s battered copy and holds it aloft and as they reach one another, Jem says “snap!” and Ash says, “Would you be interested in a picnic at the zoo sometime?”

It’s the very thing that Jem has been daydreaming — sorry, projecting possible hypothetical scenarios — about.

They introduce themselves, although by now, they’re not strangers.

“Hi I’m Ash.”

“I’m Jem.”

In unison they both say, “nice to meet you”, and realise it’s a silly thing to say and they laugh, awkwardly perhaps at first, but it soon turns to delight at having found one another again. Can’t you just see them, standing there, reaching out, shaking hands and holding that moment, neither of them wanting to let go.

Ending 3: Flinders Street

[Approx. 3 min]

If you’re getting off the tram at Flinders Street or after, here’s how the story ends.

Ash has given up on finding Jem. Ash has gone back to working remotely, and without commuting time to read, has left the book unfinished.

Weeks pass. One day, Ash re-discovers the book with the broken spine and the missing section and resumes reading. It’s a good book. One of those books that is so well written that even on a second reading you can’t quite remember the ending, and find something new in it each time.

Not far from the end, Ash discovers a handwritten note stuck in the pages:

“Avocado Tattoo on the 58 Tram, this message is for you. My name is Jem, this is my book, and here’s my number.”

Jem. What a perfect name to match those eyes.

Ash beams. Does a silly little dance in delight. And because Ash adores alliteration, Ash hears poetry, completed by Jem’s name. Jewel-eyed Jem from the tram. Jewel-eyed Jem from the tram who put pen to paper, posting a message for to Ash to receive — although Jem does not yet know Ash’s name, so Ash attempts to imagine through Jem’s jewel-coloured eyes. Jem writing the note to Avocado Tattoo. Ash can’t stop smiling.

This is the moment of discovery is what Jem had imagined, scribbling the note — the day before the pages had sailed out.

You see, Jem had wondered about finding a way to swap the books, like spies with briefcases do in old movies.

So, when the section came loose from the book on the tram, it was not entirely an accident — it was only ever a matter of time before the pages fell out. Jem could not have guessed that they would fly out the door so spectacularly — but if that hadn’t happened, Jem may have resorted to wiggling the pages like a child does with a loose tooth. Because an incomplete book could present an opportunity to swap copies, Jem thought — if Avocado Tattoo offered.

So Jem added the note in advance, just in case the possibility arose and this scenario played out. Of course, this is just one of many scenarios Jem had projected, but this is the one you, the listener, chose.

Jem has been waiting for these days and weeks, wondering what will happen next, worrying the note will have escaped the book, or the book will have been abandoned. But Jem is still hoping that Ash will find the message and make contact.

So now, Ash will pick up the phone, put in the number, take a deep breath and hit dial…

And at Flinders Street, at Stop number 1, we reach the end of this story. But the tram continues; and so do the stories of the people it carries.

Beth Atkinson-Quinton VO: Tramlines is an initiative of the Melbourne UNESCO City Of Literature Office with the podcast created by Broadwave.

Route 35 was written and read by Nadia Bailey, commissioned by David Ryding, edited by Elizabeth Flux, recorded at the State Library of Victoria, produced by Beth Atkinson-Quinton, with music by Steve Hearne.